By Alex Gapud (Staff Writer)

I strongly believe that the best scholarship does not merely present critical analysis, but ultimately draws the scholar back into an introspective gaze, to reflect on how what one has learned affects oneself.

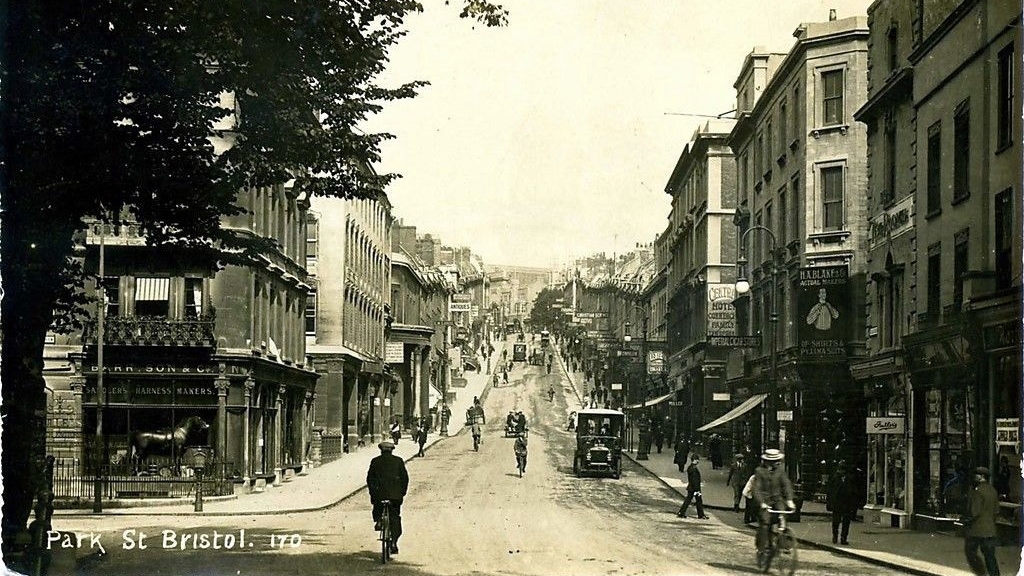

Over the past year of fieldwork, I’ve met dozens of people in Bristol, a city steeped not just in mercantile trade and maritime industry, but particularly in imperial trades substantially consisting of transatlantic slavery. While some Bristolians get very defensive toward me, an American (of Filipino descent) ‘coming over here’ and investigating how we know and understand Bristol’s past (with a particular concern on its imperial past), I often find myself quick to say one of two things, and sometimes both:

First, I’m not here to moralise on Bristol’s history one way or another. I myself am a Filipino-American, the grandson of an English professor and a high school English teacher, facts which gave my father incredible socio-economic and educational opportunities and which have eventually led to my being here. I am well aware that I am one of the beneficiaries of the colonial encounter and approach it with an ambiguous embrace.

Second, I also grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, in the former Confederate States of America, and have spent much of my life trying to understand the nuances and messiness of history where I was raised. And I’ve tried to understand this messiness from both sides.

In Bristol, I often tell stories of how it was not taught in my family that the controversial Confederate battle flag was a symbol of racism. At age 10, it was considered an honour to raise the American and Georgia state flags before school for a week. At the time, over half of the Georgia state flag was the Confederate battle flag. Through high school and university, I had come to understand the history of that flag and its connotations, although personally, I had never interpreted them with offence. Being Asian-American, yet attending a predominantly white high school and university, has a way of putting you awkwardly in the middle. Growing up, I was on the fence without having the social pressure from any one side to be pushed off: being not-white, I should have presumably been offended, but having been raised in white Southern culture, I was not – it seemed normal.

Being in the UK, the surfeit of opinion pieces about the Confederate flag in the past months have puzzled me and evoked a strange personal reaction I couldn’t quite put a finger on until recently. In today’s social media age, where not only does everyone have a voice, but feels obliged to let their opinion be known, I was hardly surprised. But, being honest, many pieces left me with a frustration I’ve struggled to understand and articulate until now: with few exceptions, hardly any of these writers (especially in the UK) are themselves Southern or have any broad experience in the South. (One article I’ll be quick to praise is Barbara Kingsolver’s column in The Guardian).

I’m not saying that an outsider to the South cannot have an opinion—they are indeed entitled to one—but many of the posts I’ve read seem to have a particularly shallow understanding of the history and debate surrounding the Confederate flag and Southern heritage. It was almost as if the debates themselves were not new, but rather, the writers were new to the debates and often portrayed this as a ‘new’ thing. Although many writers seemed surprised by the enduring presence of this debate (and perhaps rightly so), those of us who grew up in the South know that this isn’t a new issue. Growing up in Georgia, every Governor’s election during my childhood and through my adolescence until 2006 included ‘the flag’ as a talking point. In fact, one might say that the debate about the flag isn’t really news to us—and perhaps that also says something about the distance between writers and their intended audiences.

On the one hand I realise my frustration with these articles uncomfortably exposes the foremost of the ethnographer’s feared dilemmas: of being the outsider, tasked with presenting (insofar as possible) an ‘insider’s view’ or at least, a deeper understanding of what is going on, with the ever-present danger of getting it wrong. And in this regard, I realise that this is actually what I am risking with my own research on imperialism in a city like Bristol.

But there’s also the strange realisation that as an ethnographer, we’re also constantly asking questions about things that seem ‘new’ to us but aren’t at all news to our informants. When people ask me about my ‘findings’ or my ‘discoveries’ during fieldwork, I’m often at a loss of what to say. I usually say that what I’ve ‘found’ isn’t really much that anything who pays attention to heritage and has an interest in this stuff doesn’t know. Rather, the challenge of my task was to try to understand and make sense of the stuff everyone knows but takes for granted.

I realise that I am the outsider, sympathetically learning how people understand their city’s past, and trying to observe how they present and negotiate this history. Almost everyone I have spoken to in Bristol is aware of the city’s key role in the transatlantic slave trade and how vestiges of that trade—not least of all in the name of Edward Colston (the locally (in)famous merchant, politician, philanthropist, and slave trader)—remain throughout the city. But on the subject of its history of imperialism, they seem to feel rather more ambivalent, and indeed often admittedly and embarrassingly ignorant. But they are aware of the city’s role in transatlantic slavery and ongoing debates about Colston and his name. More often than not, people accept that this is part of their city’s history and believe taking down Colston’s statue or removing his name would effectively erase this history that should be remembered, not for celebration but as a warning and as a reminder of the ongoing evils of slavery today.

Nevertheless, there is a particular discomfort which accompanies my writing of Bristolians. It is perhaps the other side of the same coin as a Southern reader looking at an outsider’s understanding of one’s home, often written very far away from places like Charleston, Atlanta, or Richmond. Who am I to write of another’s history and their understanding of it, especially if I were to claim some moral high ground or detached judgment of another’s history, or if I prescribe them with some solution for their own history? If anything, this summer’s events in Charleston and many writers’ responses surrounding the flag controversy throughout the South have been a poignant reminder of the temptation among journalists and academics to claim the old colonial ethnographer’s voice when he (and it was almost always a he) wrote of ‘the natives’, of ‘those people.’

Perhaps this is a call for a sympathetic approach in ethnography that seeks to understand and present our informants and their world as thoroughly as possible, taking a humble approach to understand the sensitivities of history and heritage without ever making prescriptive demands upon them as ethnographers, and certainly never casting judgment on their understanding or interpretation of that history (even if I disagree with it).

This is, after all, not necessarily my own history and heritage, but that of another, and I think a sympathetic approach accepts that and tries to understand its sensitivity and nuance before espousing its own opinion (if it does at all). When Bristolians ask me about what I think they should do about their city’s history and its relationship with imperialism, I’m very quick to say that I don’t believe that it is my place to tell them how they ought to talk about it. But by asking them questions about their past, I am challenging them to think and talk about it amongst themselves so that ultimately, they decide how to interpret their city’s past.

But I believe this is also a call to for writers and scholars to reflect on how we write of others, and to strive for an understanding which can only come through dialogue. Earlier this summer, I visited a Canadian friend in Liverpool who researches a Ghanaian scholar and who has herself spent many years living in Ghana. She spoke of two African proverbs: ‘Only the one wearing the shoe can tell you where it pinches; but only your guest can tell you where your roof was leaking.’ How poignantly true that our understandings from one perspective are never in themselves whole or complete; that we can always draw other voices into the conversation and seek to learn more.