By Christine Huebner (Contributor)

There would be no need for more ink to be spilt on #Brexit if it weren’t for one view astoundingly missing from the post-referendum-debate: that is a view on how to move on from here. With a population almost evenly split into winners and losers, we need to ask how to reconcile those who voted ‘Remain’ and those who voted ‘Leave’ in the UK’s EU referendum. Rallying against #Brexit or demanding a repeat referendum – albeit unquestionably healthy reactions of civil society – will not help to move on. What will help is a serious dialogue between both camps, where there is a true effort to understand the multitude of reasons in favour of and against #Brexit.

A country almost evenly split into winners and losers (Electoral Commission)

A split runs through the country

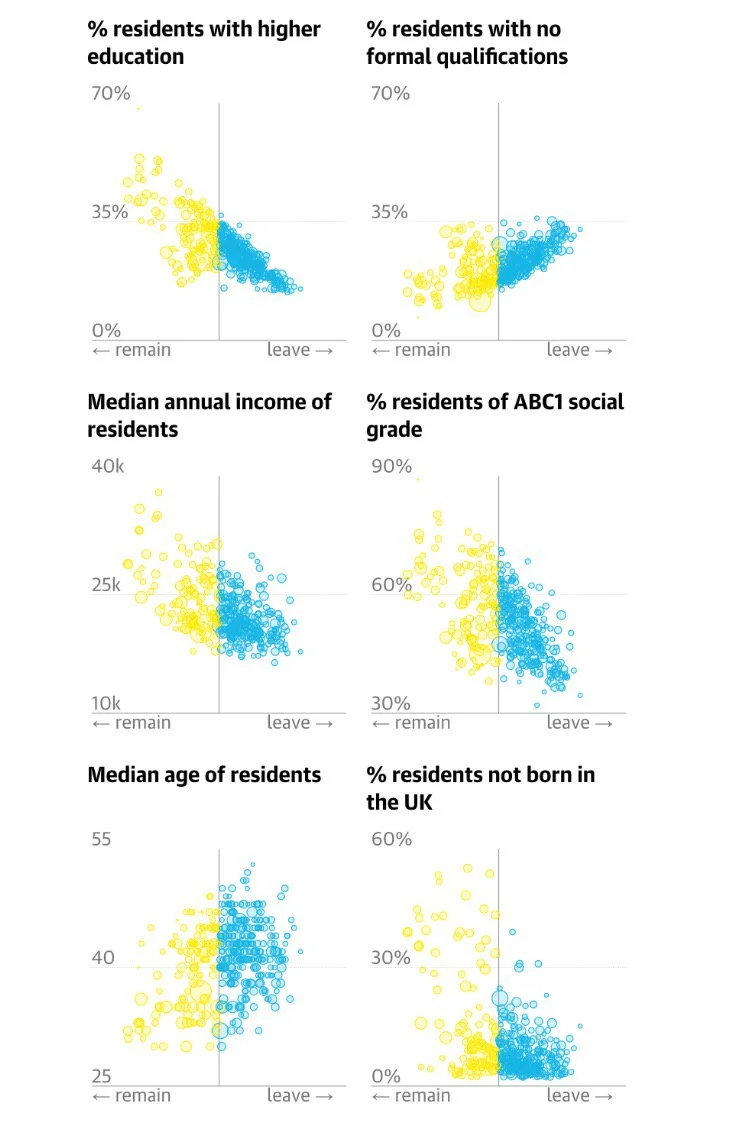

In post-referendum-Britain it seems as if ‘Leave’- and ‘Remain’-voters could hardly be further away from each other: that is in terms of geography, generation, or social class. A split runs through the country that separates the young who were more likely to vote ‘Remain’ from older generations voting ‘Leave’; the well-educated high-and mid-income earners from voters with no formal qualifications who earn less; ‘Remain’-voters living in the big urban centres from ‘Leave’-voters in the de-industrialised north, southeast or southwest of England; Scots, Northern Irish and Londoners, many of whom voted ‘Remain’ from people living in England and Wales, who more often voted ‘Leave’.

Kieran Healy: "The ecological correlations are pretty strong. Education, Class, Income, Age.“

Different realities, yet not an excuse

These statistics are now being used to justify the lack of understanding that characterises the post-referendum debate: ‘Remain’- and ‘Leave’-voters live in different realities. They never get to meet. As a consequence ‘Leave’-voters only know other ‘Leave’-voters and ‘Remain’-voters only see messages of other frustrated ‘Remain’-voters in their social media feeds. Hardly anybody is able to understand who the people behind these votes are and what their reasons were.

Yet, the tale of the dividing lines is merely an excuse for a lack of dialogue between the ‘Leave’- and the ‘Remain’-camp. After all, these are averages over 46 million voters. There are indeed students who voted ‘Leave’ just as there are ‘Remain’-voters in the north of England. And even in Scotland not everybody is a die-hard fan of the EU: 1 million people (that is 38% of Scottish voters!) voted to leave the European Union. It should not be so difficult to find and ask them why they did.

In a land where no one understands

The true reason is that no one is making any effort to understand the reasons behind voting ‘Leave’ or ‘Remain’. The appalling quality of the political campaign ahead of the referendum has given way to hostility, resentment and a general lack of understanding. Especially for disappointed ‘Remain’-supporters it is all too easy to argue that ill-informed ‘Leave’-voters took stupid decisions against their own interests. Yet, this view is not helpful at best and extremely patronising at worst.

With 17 million voters in favour of leaving the European Union, there cannot be one single reason to vote ‚Leave‘. Indeed, voters may have been ill-informed. And some of them may even have taken a different decision on the basis of other information. But there are many other reasons why people voted ‘Leave’:

- some of them are about economic and political / cultural marginalisation,

- others are about the fear and consequences of globalisation, and

- about that awful feeling of not being control.

- And then there are those who used the referendum to express their dissatisfaction with the current government or

- simply a different vision for the future of the UK.

It’s truths, not facts that matter

In a democratic system it does not matter whether we deem these good or bad reasons, factually right or wrong. What matters is how we engage with them. Liberal thinker John Rawls argues how at its essence democratic deliberation is about “reasons aimed at consensus”.[1] In that, these reasons do not have to coincide with what is factually right – as long as they justify and help us understand why people feel the way they do.

With many ‘Leave’- and ‘Remain’-voters living in different realities, there are multiple truths about the consequences of a #Brexit. If, for example, ‘Leave’-voters believed the argument on the negative consequences of immigration to be true, ‘Remain’-voters need to take that truth seriously rather than dismiss it as factually incorrect. This is undeniably easier to do when facts and reasons coincide. However, even when they do not (or maybe especially then) we need to try and understand the truths on either side to work towards a consensus. Democratic acting is about seeing one’s fellow citizens as rational autonomous agents capable of making judgements about what to believe.[2]

Loser’s consent and how to move on

Once an election such as the UK’s EU-referendum is over, the legitimacy of a democratic decision hinges on the losers’ consent: that is the willingness of those losing in an election to overcome any bitterness and resentment and be willing, first, to accept the decision of the election and, second, to continue playing the democratic game.[3] In that, playing the democratic game does not mean demanding a repeat referendum; it means working towards consensus and moving on. A simple what-if-scenario illustrates this: imagine the vote would have turned out 52%-to-48% in favour or ‘Remain’. It is easy to envision how the winning ‘Remain’-camp would have asked of the ‘Leave’-campaigners to accept the public’s decisions and to stop rallying in favour of #Brexit.

The normative question: what should happen next

The appalling quality of the political debate and a significant lack of loser’s consent demand that we start thinking about how to reconcile ‘Leave’- and ‘Remain’-voters sooner rather than later. A serious engagement with all views in this debate is called for. Here are some ideas on how this can happen:

- Politicians in any part of the UK (yes, that includes Scotland!) need to engage with both ‘Leave’- and ‘Remain’-voters. They need to listen, understand and talk about the various reasons that convinced citizens to vote either way.

- We need to create spaces for ‘Leave’- and ‘Remain’-voters to interact with one another and discuss their concerns. This can happen at the local pub, but also at a regional or even national convention. Although it may be more or less difficult to find them, there are voters of either side in each region.

- Given the dividing lines, the national media has to play a role in the process. While the British press is not exactly known for its conciliatory tone, its role may be more important than ever. Also the BBC has the potential and reach to act as a voice of reason for all.

It is almost like what we need is a ‘Leave’- and a ‘Remain’-campaign all over again, just now in the much-better-quality-edition.

Christine Huebner is a PhD candidate at The University of Edinburgh’s School of Social and Political Science. Her research interests revolve around the relationship between citizens and their political community, focusing on questions of political participation, political belonging and legitimacy. She is also a partner at d|part, a non-partisan think tank committed to research and public debate on the topic of political participation.

This piece has previously been published on the d|part blog.

[1] John Rawls. 1993. Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

[2] Michael P. Lynch. 2012. Democracy as a Space of Reasons. Truth and democracy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

[3] Christopher J. Anderson, André Blais, Shaun Bowler, Todd Donovan, and Ola Listhaug. 2005. Losers‘ Consent: Elections and Democratic Legitimacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.