By Gill Davies (Fieldwork Prize Runner Up)

As a conscientious 1st year PhD student preparing for fieldwork, I diligently reviewed the relevant literature. Since I had chosen to effectively intern with two British NGOs while undertaking ‘participant observation’ of their work, the writings of David Mosse seemed particularly useful. He is an anthropologist who spent over 10 years consulting for the UK’s Department for International Development in India, before writing a frank and critical ‘insider’s’ account of the development industry. After reading this and various methodology guides, I began my field work feeling fully conversant in both the benefits and dangers of being an insider: enhanced access to the internal workings of my case study organisations, yet risks of becoming so absorbed in them that I would unknowingly lose any objectivity as a researcher.

Over the first few months in Kenya with the British NGO Global Village Energy Partnership (GVEP), I slowly got to grips with their various activities to support small, local energy businesses. I was based in Nairobi which, it quickly became apparent, is the NGO hub of the world: it is notorious for traffic jams full of big white 4 wheel drives with aid agency names emblazoned on the sides. By contrast, a visit to Kibera, Africa’s largest slum, showed the other face of Nairobi, its ramshackle buildings and narrow earth streets crammed with people on foot.

Feeling overwhelmed by the city’s obvious contrasts and not yet sure about the role of development organisations in all of this, I jumped at any chance to head out in GVEP’s own white Land Cruiser to visit their rural ‘entrepreneurs.’ These were Kenyans who made and/or sold energy products for cooking or lighting. GVEP gave them business training to help them improve quality and expand production and sales. Many of the entrepreneurs made efficient cookstoves from clay collected from local river banks, moulding it into liners to be fired in kilns and clad with sheet metal. Through their increased thermal efficiency (by comparison with open fires or metal cookstoves with no clay lining) these cookstoves reduced both the quantity of firewood or charcoal needed for cooking, and the amount of smoke produced. Given that smoke inhalation has been linked to high levels of respiratory diseases in developing countries, I was confident that any effort to make cleaner cooking technologies more widely available had a strong ‘developmental’ claim. This was further helped by my conversations with entrepreneurs who found GVEP’s support extremely valuable.

By the time I left Kenya, I had become firmly committed to GVEP’s mission of making cleaner energy products available to all. Moving to their Kampala office in Uganda, I found an equally friendly and motivated team as in Nairobi. Since they were all Ugandans, any preconceptions I’d had of NGO workers all being exorbitantly paid expats once again fell flat.

Yet as I became increasingly absorbed into the development world and its obviously noble causes, it took some time to notice that it was shaping my conceptualisation of the people who were intended to benefit from charitable activities. My literature review for the first year board paper was full of critique of development projects creating narrow dichotomous labels for ‘charity-givers’ and ‘charity-dependents’, ‘aid workers’ and ‘beneficiaries’, ’them’ and ‘us’. In my methodology, I had described how I would objectively record and analyse any incidences of this that I came across. However, I soon found myself inadvertently trying to represent prospective energy product buyers as development beneficiaries.

I realised this while staying on an island in Lake Bunyoni in western Uganda, during a week travelling with my boyfriend who’d come to visit for New Year. With the assistance of GVEP I had now visited many cookstove producers and some of their happy customers. Yet, because everyone was keen to show me their excellent cookstoves in use, I had still never had the opportunity to see a traditional three-stone fire being used for indoor cooking. The constant vilification of these in any development literature or conversations had built a picture in my mind of horrendous displays of billowing smoke in tiny windowless rooms, surrounded by choking women and children, eyes streaming.

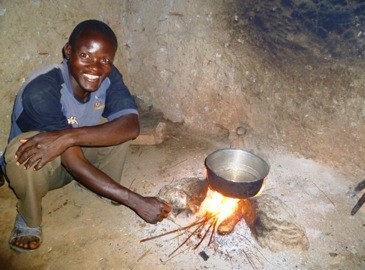

I finally got to see one in action when a local family on the island invited us for dinner in their home. As we settled in, our host Jared skilfully lit his three-stone fire with carefully placed twigs, in readiness for a huge pan of crayfish freshly caught from the lake and the inevitable posho (Ugandan maizemeal staple). Once cooking was underway, I naturally asked to take a photo, excited that I would finally be able to illustrate my thesis with a poor Ugandan farmer being exposed to smoke inhalation. Jared, however, happily and perhaps unsurprisingly did not seem to have this problem at the forefront of his mind. In fact, he actually seemed to be enjoying using his fire to cook his visitors a rather tasty smelling meal. Each time I tried to take a photo of him at the dangerous and burdensome fireplace, he frustratingly looked up and gave me a beaming smile. For a moment I thought of specifically asking him not to smile, but at the time I dismissed it as impolite. On later reflection, I realised that it would not only create a false photo to illustrate my work with, but that I had become so fully entrenched in the aim of development that it had narrowed my perception and intended portrayal of situations to fit that particular agenda.

It also showed the validity of some advice that I had been given by an experienced fieldworker prior to my own trip – assume that everything is relevant, at all times, and worthy of recording. Some of the most insightful parts of my final thesis have now been constructed from events like this, outside of my standard working time with the NGOs. I’m therefore very glad that I took their advice.

Gill recently completed her PhD in African Studies, looking at how development organisations are trying to increase access to modern energy services in sub-Saharan Africa. Having successfully passed her viva, her next steps are to start work on some journal articles and devise further research plans. She hopes this will involve more travelling!

All pictures are the authors own unless otherwise stated.